BILL NASSON is impressed by The Café de Move-On Blues, a new book by Christopher Hope that offers an even-handed, clear-sighted and vividly-drawn portrait of the pain and paradoxes of post-apartheid South Africa.

The front matter of Christopher Hope’s latest book displays the distinctly un-neighbourly sentiment of a Pastor Ngobeza who, in the 1920s, pronounced, ‘White people have no right to be here and the White man who says he has got a farm here must roll it up, put it on a train and spread it in the land that he comes from’. It makes an uncomfortably blunt start to The Café de Move-on Blues: In Search of the New South Africa and, in a way reminds this reviewer of a very much earlier book in this exploring tradition. In 1877 the English Victorian novelist, Anthony Trollope, produced South Africa after sniffing his way around its colonial parts. ‘South Africa’, he concluded, ‘is a country of black men and not of white men – it has been so, it is so, and it will be so’.

Trollope’s laconic vision was a deliberate rap over the knuckles of those deluded white settlers who imagined themselves to be living in an African version of Australia or a sunlit New Zealand. Nowadays, one might perhaps be tempted to envision the conservative-liberal Anthony Trollope and the EFF’s fascist Julius Malema as an unlikely pair of historical time-travellers, orbiting a country which, like Ireland, is notoriously inclined to remember the future and imagine the past.

Although The Café-de-Move-on Blues may, at first glance, appear to be a volume in the fairly well-worn tradition of touring the land to report on its grim realities and to tell The Story of South Africa, this is a new classic which has to be distinguished from earlier vintages such as Allen Drury’s A Very Strange Society: A Journey to the Heart of South Africa (1967) and Joseph Lelyveld’s Move Your Shadow: South Africa Black and White (1986). Firstly, and obviously, Hope’s subject is not the South Africa of high water apartheid but of its post-apartheid present. Secondly, and most importantly, his book is not the work of an outsider reporting on the South Africa drama, as the author is not some touring American journalist. The book is, instead, an insider’s immersion in South Africa, trying to get to grips with, as he puts it so masterfully in its preface, a country ‘where the more you know, the less you understand, but that in no way lessens the need to go on looking’. This lets you know, if you’d not already got it, that The Café de Move-on Blues is not just about South Africa as a place but also – far more – about the loaded character of today’s South African nation.

Lastly, who better than an acclaimed South African novelist, non-fiction writer and poet to capture the contemporary texture and sinew of this ‘mad and absurd’ land. In this, not the least significant thing about Christopher Hope’s shrewd gaze is his personal history. With writings banned, he was harried into exile overseas in the 1970s from where he continued to show South Africa’s apartheid rulers the finger, with award-winning fiction such as the deliciously-titled A Separate Development and Kruger’s Alp. Freed from its suffocation, from distant places (like France, where he now lives) Hope has been able to benefit from the coolness of distance while all the while maintaining an exasperated yet very soft spot for the land of his birth.

Equally, as anyone will immediately appreciate, The Café de Move-On Blues echoes with the author’s intimate, sure-footed steps across known local soil, for he certainly knows his onions, both old and new. So, when Hope leads you through Pretoria, you encounter not only that city’s hardy perennials, the blossoming jacarandas. You also come across the predictable political seasonality of its street names. For instance, what is now Jan Shoba Street was previously Duncan Street. ‘Jan Shoba’ was a member of the Pan-African Congress’s woeful Azanian People’s Liberation Army and owes his municipal elevation to the ruling nationalist party’s fondness for patronising humbug. As Christopher Hope notes, ‘those who get to change the names of suburban streets felt obliged to throw a bone’ to their old PAC rivals, propelled by the ritual reflexes of ‘transformation’ and ‘inclusiveness’. Thus, down came a British Governor-General of the Union of South Africa, Sir Patrick Duncan, and up went the PAC freedom fighter, Jan Shoba (who was, incidentally, murdered in murky circumstances in 1990).

As The Café de Move-on Blues observes of such memorialisation, you might well say, fair enough. But you’d only say that if you had a cavalier approach to the country’s history. Hope, on the other hand, is an author who passes the test of history as assuredly as he does the test of travelogue. He points out that Duncan’s son, also Patrick, ‘was a rare and remarkable man in whose name you might name boulevards and airports’. A passionate believer in equality, a member in the 1950s of the Liberal Party and banned in the early 1960s, Duncan was the first white person to join the PAC of Comrade Jan Shoba, representing it abroad for a time and spending the remainder of his spirited life in exile. Had the name-changing commissars of Tshwane taken any account of this striking ‘Duncan’ significance when fiddling with street signs? The sound of such ironic acts of ‘decolonisation’ is surely deafening. For the thing about city streets is that they are mostly not one-way, especially in this country, where the route to so many destinations is a maze. In a myriad of ways, including its reflections on the stage-management of public symbolism, The Café de Move-on Blues is a model of truth and reason at a time when the contagious power of a spurious racial nationalism trumps a civilising enlightenment.

Of course, this is a blight of the current world, not simply that of South Africa. It is a world in which, Christopher Hope writes, ‘borders and boundaries and patrols’ are carrying the day, from America’s Mexican border to Britain and the EU. Still, when it comes to this country, has it not been ever thus? As the author emphasises in his preface, given its ‘long hard night’ of ‘antediluvian racial dementia’, South Africa has the history to be awarded a gold medal for its assiduous hedging of ‘ethnic difference and distance, ethnic exclusivity, tribalism, partition, separation and apartness… keeping others out or ourselves in’.

In this respect, The Café de Move-on Blues can be read as a kind of coda to Hope’s 1988 White Boy Running, an intensely personal portrayal of his first return visit to South Africa in over a decade, another forensic read in which he wields a scalpel while looking his then late-apartheid country straight in the eye. There, he peeled open a place of ‘horrifying comedy’, concluding that it’s a country over which ‘the sun is shining but it does not fool anyone. This is funeral weather’. Funereal strains are also to be found in Hope’s earlier poetry. In the aptly-titled ‘Notes for Atonal Blues’ which wraps up his 1981 collection, In The Country of the Black Pig, he ponders a land ‘already three-quarters desert’, with its dominant white society blanketing itself against apprehensions and insecurities, doggedly ‘dug in for the duration… while stocks last and wherever grass is mown’.

In its sketching of the subsequent New South Africa, The Café de Move-on Blues finds it still dug in for the duration, steeled by its time-worn ‘amnesia and careless forgetfulness’, while finding time to assault the marble and granite of colonial heritage. Even though you can’t hurt the dead, you may as well have a go at offending some of the living. In taking as his central thread the recent bout in toppling, defacing and frothing over South Africa’s statues and monuments, Christopher Hope’s book is, in part, a distinctive – and distinguished – critical chapter in the ongoing story of today’s culture wars. His inspiration started, as he tells us, ‘by chance, one autumn morning in 2015’ when he happened to be in Cape Town, passing the university, and his eye was caught by a seething crowd ‘mobbing the large statue of a seated man’. He found himself witnessing a rare moment, a frenzied and ‘angry crowd lynching a statue’, with the university’s student protestors ‘playing their part as priests of the tribe, solemnly punishing’ the transgressor’ in an impromptu ‘public act of exorcism’. All the while their ‘opened iPads, like prayer books’, dangled ‘in front of their faces’, recording the ‘excommunication’ and ‘execution’ of Cecil Rhodes, and then, with ritual predictability, ‘each other and then themselves’. It signalled the rise of the Fall.

This is all laid on with an even-handed brush. In the author’s view, Rhodes is anything but rosy, and he ranks him down in the gutter on the historical scale of white colonial arrogance, brutality and greed. But at the same time, equally vigorously, he insists that he is also ineluctably ‘part and parcel of who we are and cannot be got rid of’. In a terse judgement, Hope wonders that if ‘reliable old heroes were now the new villains, could one redress past injustice by airbrushing such figures from the record ?’ Ultimately, you might wish to ‘forget Rhodes, but his ghost will not forget you’.

One can only but imagine the republican Boers of Paul Kruger and the Afrikaner nationalists of D.F. Malan and H.F. Verwoerd smirking in their graves at this mighty blow against so detested a symbol of British imperialism. They, too, had every cause ‘to detest the man’ and what he embodied. For all that, though, South Africa’s previous Twentieth Century regimes had left statues standing, ‘no matter who it was’ that they ‘remembered or offended’. But virtually everything of what was standing (even a Port Elizabeth war memorial to horses) was now fair game, as it had become open season in ‘a war of words and images’. Or, in effect, the demolishing of Rhodes was the opening shot in a shrill campaign waged against the dead, a war to cleanse places of the faded commemorative traces of ‘identifiable enemies’, never mind that they had long ago shed any magnetism as pillars of pilgrimage for white South Africa to glorify its colonizing past.

Certainly, in that sense, the University of Cape Town assault had been a stalking horse, for as ‘everyone knew’, the frenzy ‘wasn’t really about Rhodes’. It was about purging the country of its imperial and colonial pedigree, and rebelling against a past that was continuing in the present, that of a haughty ‘”White” oppression. Twenty-odd years after the rainbow nation’s rain of freedom, South Africa was now heading into the acid rain of a pugnacious black nationalism,

With the ‘deplinthing’ of Rhodes the first victory for the text-obsessed student avant-garde of the discontented, The Café de Move-on Blues takes us on a looping journey right around the country – the book includes a nice map depicting just how ambitious was the author’s pilgrimage to the spots of ‘mute assaulted statues’. He takes in far northern Limpopo, heads through Mpumalanga down into Kwazulu-Natal, saunters onwards both along the coast and inland through the Eastern Cape before ending up where he began, in Cape Town. There he finds, on the slopes of Devil Peak’s, the next chapter in the ruin of Rhodes. At the Memorial which bears his name, the bust had been targeted by vandals who ‘had attacked the head and knocked off its nose’. Almost relishing this a little, Hope wishes that ‘the noseless Rhodes survives’, as it is ‘so eloquent and unforgettable and portrays something of who we are and how we got this way’.

In the several parts of its travels along the roads between Rhodes, Café de Move-on Blues provides a taut string of vignettes which turn up evidence of the meanings of South Africa just about everywhere its author looks. Where what’s depicted isn’t desecration, it’s often clouded in controversy. The West Coast Fossil Park contains the prehistoric skull of a Stone Age Saldanha Man who used to be called Hopefield Man. ‘What makes him very alarmingly up-to-date’ is that he appears to have been murdered, making him ‘one of us’. In the vicinity of Kimberley, there is the Anglo-Boer War concentration camp cemetery at Orange River Station, with the names of its white dead ‘recorded and remembered’, while for black people who perished in the same war there are ‘fewer graves and scant memorials’. Turning sombre, Hope recognises this as ‘a very South African situation; as familiar as it is forlorn’.

Along the way there are the other usual suspects, like Jan van Riebeeck, Hendrik Verwoerd, Mahatma Gandhi, Paul Kruger, and Nelson Mandela, all deftly handled and explored with polished insights and engaging wit. There is even space for spots such as the Rand Club, Fraserburg’s ‘secret monument’ (which I shan’t reveal!), and Dainfern estate, that much-mocked settlement sustained by its belief that ‘this isn’t a penitentiary; it is paradise’. His journey is told with such ease and assurance that it feels almost companionable, as if one were meandering about with him. As we roll on through the gallery there is plenty over which to pause, including surprises. In Durban, the statue of King George V, a stupid monarch associated only with collecting stamps and shooting deer, had been splashed with paint and adorned with an ‘End White Privilege’ placard. A faded and all but forgotten British royal had become Johann Rupert.

The Café de Move-on Blues also reminds us that when South Africa’s memorials are more poignant than political, they remain forgotten. Who today remembers ‘Happy’ Sindane? He was ‘the lost boy’ from 2003 who popped up claiming that he’d been kidnapped from his white family and raised in an African township by a family which had put him to work as a slave. Briefly a celebrity, he rose like a comet only to fall not only to earth but into it, murdered a few years later by a companion on his drinking sprees. Earlier, Happy had been done in by DNA tests which revealed that he wasn’t the son of a wealthy white family who had been ‘stolen by the maid’. He was, instead, ‘the son of the maid’. Today, the ‘ugly duckling’ who ‘never made it into a swan’ is flattened by the weight of ‘an over-large monument in a far-away country graveyard’ which no-one visits. In one of this book’s most sombre and searing sketches, Hope finds Happy to be ‘the heart of the matter’, a tragic and tortured Cinderella ‘who is who we are; or he is what we have done to ourselves’.

Wherever it moves, The Café de Move-on Blues trails historical musings to tease the imagination of the general reader. A number of these fix on the fortunes of the Khoi and the San, and one can’t but wonder whether these marginal men and women may become the stuff of the author’s next piece of non-fiction. If so, I hope that it comes with something which this present book sorely lacks, an index.

The history here jostles alongside occasional accounts, sometimes tart, sometimes touching, of the author’s interactions with an assortment of South African characters, such as Theo, the Johannesburg vet, and a radical student, ‘Thandi’, at ‘the university currently known as Rhodes’. These exchanges come across as nothing so much as a dialogue of the deaf, as Christopher Hope’s sceptical probing hits a wall of convictions and certainties. And, as is surely to be expected of a book, its writer does not skim the fiery fate of books (and paintings) at the hands of rampaging student arsonists on some university campuses, as they fanned out to split the rocks of ‘Whiteness’ and ‘Coloniality’. As always, Hope’s judgement is crisp and salutary, concluding that there could be ‘no winners’ in ‘such bonfires of the inanities’.

Ultimately, this is a cautionary and distinctly apprehensive love letter to the mad and absurd country the author knows so well. Its tensions and ambiguities are reflected in the title of this book. Its cover is a 1964 David Goldblatt photograph of a decrepit mobile food and drink stall, a ‘café de move-on’, as the apartheid regime’s police were constantly shoving it on from place to place. It is a haunting metaphor for Christopher Hope’s journey. Several decades ago, he had a conversation with Oliver Tambo in London and when the subject turned to the sadness of the constant push of the café de move-on, the ANC leader declared his wish for a land where no one was turfed out, where no-one would ever feel the menacing strains of ‘the move-on-blues’. Yet, as he tells us in his final sentence, ‘whichever way you play it, I hear the music’. Then, as now, a sense of common fellowship and decency is rarely, if ever, enough.

The Café de Move-On Blues is published by Atlantic Books. Bill Nasson is Emeritus Professor in History at Stellenbosch University.

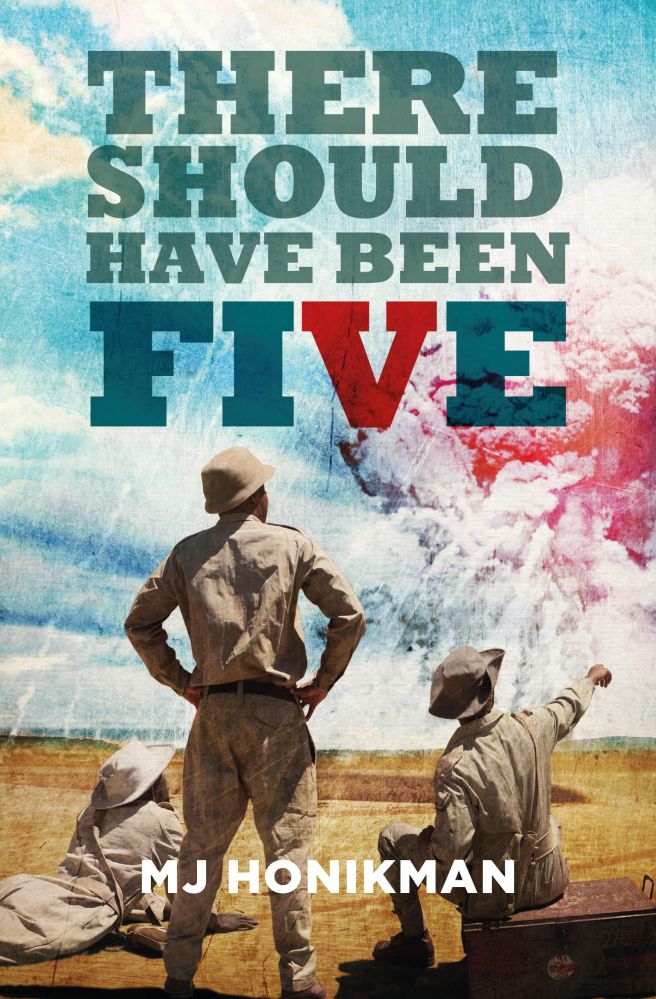

Should you ever judge a book by its cover? You have my blessing to do so with MJ Honikman’s There Should Have Been Five. A first glance at its quietly dignified and intriguing cover design is enough to excite curiosity and interest. The staged front photograph portrays three dark-complexioned and khaki-clad Allied servicemen from the rear. They are gazing across flat and brown desert terrain towards a distant explosion which is sending a massive red-and-white ice-cream cone topping oozing out against a streaky blue sky. Who were these men, and where were they? What was the eruption that had caught their gaze?

Should you ever judge a book by its cover? You have my blessing to do so with MJ Honikman’s There Should Have Been Five. A first glance at its quietly dignified and intriguing cover design is enough to excite curiosity and interest. The staged front photograph portrays three dark-complexioned and khaki-clad Allied servicemen from the rear. They are gazing across flat and brown desert terrain towards a distant explosion which is sending a massive red-and-white ice-cream cone topping oozing out against a streaky blue sky. Who were these men, and where were they? What was the eruption that had caught their gaze?